More than a year after being signed into law, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act remains among the most well-known and hotly debated achievements of President Donald Trump’s administration. As the first tax filing season under the new law approaches, scrutiny and discussion of its major changes will only increase. However, one major component of the TCJA that could represent an opportunity for real estate professionals has largely flown under the radar, until recently.

The headline-grabbing changes introduced by the TCJA include lower rates for personal and corporate income, as well as a variety of revisions, deductions, and credits. But one of the more unusual aspects of the federal tax overhaul, on page 130 of the nearly 200-page bill, could be just as economically significant, and particularly so for real estate.

Known officially as Section 1400Z, the law grants federal and state officials the authority to designate “Opportunity Zones” in local areas throughout the U.S. Ultimately, the goal is to stimulate investment in chronically neglected urban and rural areas by introducing new tax breaks for investors tied to projects in these designated spots.

“When it comes to Opportunity Zones, it will be off to the races to capitalize on the program,” said Jaime Sturgis, founder and CEO of Native Realty in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “The federal guidelines will be well established, so the capital being raised will start to be deployed.” But even as projects benefiting from these tax law changes begin to bloom, several questions about Opportunity Zone legislation remain unanswered.

How it happened

Senator Tim Scott (R-S.C.) is credited with introducing the Opportunity Zone provisions in the final draft of the TCJA. Based on a bill he had previously co-sponsored, the idea behind Opportunity Zones had bipartisan support from the beginning, and eventually earned attention from the private sector thanks in part to Sean Parker, a prominent Silicon Valley venture capital investor known for his early involvement in Facebook and Napster. The Economic Innovation Group, a Washington, D.C. think tank funded by Parker, estimates that one in six Americans lives in a “distressed community,” defined as an area where the median household income is lower than average and the poverty rate is much higher. Census data show that employment opportunities fell by 6 percent in these communities between 2011 and 2015.

Parker and Sen. Scott worked to devise what would eventually become the legal framework around Opportunity Zones written into the 2017 tax bill. The Economic Innovation Group estimated that before the law passed, American corporations and individuals were sitting on some $2 trillion in unrealized capital gains. Under the current law, investors would have to pay taxes at the federal 20 percent rate, plus a 3.8 percent surtax in order to take possession of those gains. In very large transactions, like major real estate sales or stock trades, that could incur a multimillion-dollar tax bill.

How it works

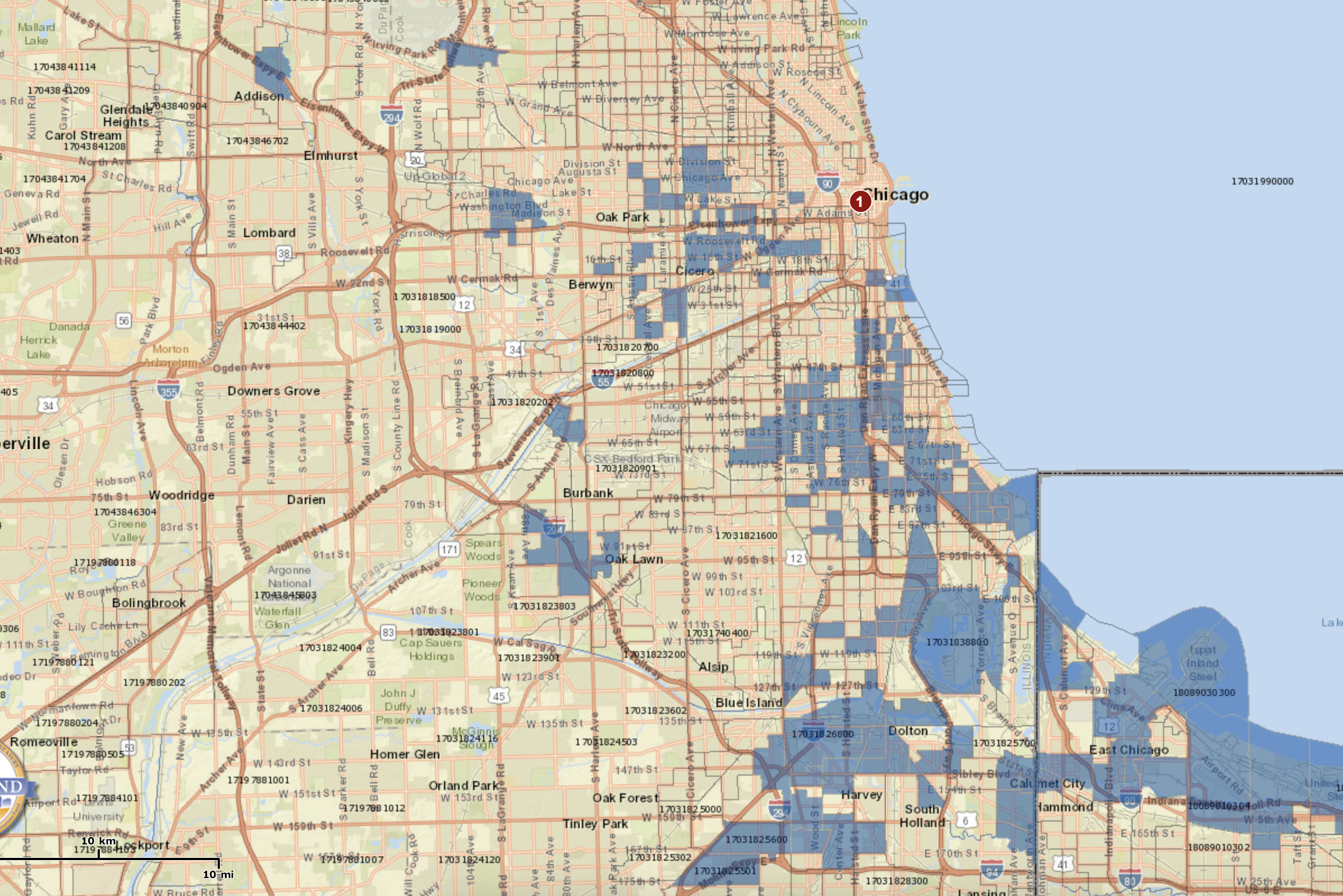

After tax reform was signed into law, the Treasury Department worked with officials at the state and local levels to designate specific census tracts as official Opportunity Zones. Now covering swaths across all 50 states, these are generally places where poverty rates are much higher and household incomes are much lower than that of their neighbors’.

The new law steers capital investment toward these communities by way of a tax incentive. Investors who earn capital gains (from selling assets like stocks or real estate) can choose to defer those earnings into a Qualified Opportunity Fund. Under the supervision of the Treasury Department, those funds will then invest in projects within Opportunity Zones that fuel economic growth, job opportunities and other goals for which investment capital would be hard to secure.

The Opportunity Zone legislation allows taxpayers with unrealized capital gains to defer those proceeds into a qualified fund that will then invest in growth-focused projects in those areas. Once those deferred profits have been held in a Qualified Opportunity Fund for at least five years, 10 percent of the deferred profit can be excluded from capital gains tax. By waiting at least 7 years to cash out of a QOF, the IRS will grant a 15 percent exclusion. Finally, if the investment is held in the QOF for at least 10 years, investors can cash out without incurring any capital gains taxes at all.

Early buy-in from developers, investors

While the details of the rules are still being clarified by the IRS, investors have already begun raising capital for their own QOFs. Goldman Sachs and PNC Bank were said to be among the largest financial institutions to get a head-start on raising their own funds. Other commercial real estate investment firms throughout the country have joined the rush to attract funding or even purchase properties in Opportunity Zones ahead of even greater interest to come. The Wall Street Journal reported that based on data for the first three quarters of 2018, property sales in the zones have spiked 80 percent, and land prices have risen around 50 percent over the same period.

The Trump Administration and Treasury Department officials say the total amount invested in QOFs could soon reach $100 billion or more. In December, the president signed an executive order to direct even more federal resources to the Opportunity Zone cause, including the establishment of the “White House Opportunity and Revitalization Council” to unify 13 federal agencies in the effort.

Questions about accountability

Opportunity Zones are unique in their bipartisan nature: a potential safe haven for tax earnings among the wealthy that also helps fund development in low-income communities. But the rules and their implementation so far have already come under scrutiny even among groups that support the idea generally.

Among the primary concerns is that Opportunity Zone rules won’t necessarily last long enough for investors to fully benefit from them. That’s because, along with all the other tax breaks and rule changes included in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, they are set to expire by 2026 unless renewed or revised by Congress. It’s possible that a law will be passed before then to keep specific rules of the TCJA in place beyond that point, but it’s not a given.

Other critics have argued that many state-designated Opportunity Zones fall within urban or suburban areas that are far from economically disadvantaged. For example, researchers from the Brookings Institution found that several zones fell within some of the nation’s most prominent “college towns,” where upwards of 99 percent of residents were enrolled in college. While poverty rates in these areas are technically high, it’s not for the same reasons truly distressed inner-city or rural communities find themselves imperiled. The New York Times also pointed out that many of the sites selected by Amazon for its planned headquarters in Long Island City, Queens, fall within designated Opportunity Zones. These examples suggest that not all designated Opportunity Zones were completely lacking in investor interest before the new tax break was introduced.

Community development advocates who support the law’s basic goals also hope federal regulators continue to release more specific guidance and limits around Opportunity Zone investment. As the Brookings Institution points out, the most recent rules allow QOFs to fund almost any kind of development, with only a few exclusions for projects like casinos and other “sin businesses.” Their report calls on federal regulators to establish more stringent “guardrails” for states and local governments to follow to ensure QOFs deliver the real benefits to local constituents. The Brookings Institution also called for a greater level of transparency between QOF investors and the public, holding participants accountable for the consequences and benefits of the projects they help fund.

“If we don’t evaluate programs rigorously, clearly they are going to look like they work—even if they don’t,” the Brookings report authors wrote. “And that threatens the efficacy not just of the Opportunity Zone program itself but the capacity to improve the next round of place-based programs.”