As a Black woman, Michelle Mills Clement could not have been CEO of the Chicago Association of REALTORS® (CAR) 50 years ago. This is something she acknowledged on stage on April 11 at The DuSable Black History Museum.

“Shame of Chicago” panelists Emily Drake, Michelle Mills Clement, Bruce Orenstein and Chris L. Jenkins.

Clement was introducing “Shame of Chicago, Shame of a Nation,” a new, four-episode documentary series about the history of housing discrimination in Chicago: a history which fuels the racial wealth gap still present today. She also acknowledged the association’s own role in that longtime discrimination.

As the documentary went on to show, local real estate associations promoted restrictive covenants to keep Blacks out of predominantly white neighborhoods. “Our association has been on the wrong side of history,” Clement said. This is why CAR, in part, sponsored “Shame of Chicago,” providing funding to the production and hosting the DuSable screening event.

There, CAR played episode two for attendees, “The Chicago Plan.” It provided an overview of housing discrimination in Chicago, beginning with the City Beautiful movement, which gained traction after the World’s Fair in 1893, and continuing up to the 1950s.

Episode one, “The Color Tax,” will premiere on WTTW on April 18 at 9 p. m. The following three parts of “Shame of Chicago” will air weekly.

In the meantime, we wanted to re-share our 2016 article by James F. McClister, “Black and white city: How race continues to define real estate in Chicago.” The piece provides a deep dive into the historic roots of Chicago’s segregation. A companion, if you will, for the “Shame of Chicago” series.

Black and white city: How race continues to define real estate in Chicago

In 1955, Albert and Sallie Bolton, an African American couple living in Chicago’s “Black Belt” on the South Side, purchased their first home for $13,900. A single-family property in the city’s Hyde Park neighborhood, the home seemed like an opportunity – the couple had four children, and the area’s schools were among the city’s best – but the Boltons were, in fact, victims of contract buying, one of the many methods of housing discrimination that would come to define the Chicago of today.

Little did the Boltons know that the white real estate agent representing the home, Jay Goran, had purchased the home himself for only $4,300 a week before. Or that additional fees and costs would be added to the home’s monthly payments after the purchase. Or that after they fell behind on a payment, Goran would immediately start the eviction process, and they would stand to lose the $3,000 they had invested in the house. Their troubles are told in detail in “Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America” by historian and Rutgers professor Beryl Satter.

The Chicagoland region’s problems with race are well documented. What is less known is how closely racism and housing policy are intertwined, and how things like restrictive covenants, redlining and contract buying were the city’s (and the North’s at large) answer to the Great Migration. And while interventions at various levels and various times have helped disavow the practices once called “prudent planning,” their effects remain as real as they are stark.

In order to even begin to heal the decades-old racial boundaries carved deeply into this city and its suburbs, every agent must understand their historical context. Past policies and prejudices, both local and federal, have influenced housing and real estate in Chicago at every level, and as you will read in our cover story, effective solutions require a sobering look at the causes of the outcomes we live with now.

The Seeds of Segregation: Ordinances, Restrictive Covenants and Blockbusting

Chicago was not the first Northern city to attempt segregation: that was Baltimore, in 1910. It established special zoning districts that allowed for the official separation of Blacks and whites, and inspired the adoption of similar ordinances throughout the country.

In the 1917 U.S. Supreme Court case Buchanan v. Warley, the Court ruled exclusionary zoning laws were unconstitutional. It was a landmark decision. The ruling barred municipalities from implementing similar policies of segregation. But it did not end the push to separate the races. Instead, it moved cities and real estate groups – particularly the Chicago Real Estate Board (CREB at the time, now known as CAR) – to innovate in their efforts to contain the urban Black population.

The result was policies that allowed cities to skirt judicial precedent: organized block clubs, which ensured that homes were not sold to Black consumers outside of approved areas; and agreements called “restrictive covenants,” stipulations that were written into housing deeds that barred the sale of homes to Nlack consumers. Restrictive covenants began in the 1920s and extended into the ‘50s, while the CREB’s block-club methods became national policy, as the National Association of Real Estate Boards (which became the National Association of REALTORS®, or NAR, in 1972, not to be confused with the National Association of Real Estate Brokers, or NAREB) and other city boards adopted the strategy.

“CREB strongly encouraged local communities to organize and put in restrictive covenants,” said Satter, who teaches at Rutgers’ Center for Migration and the Global City. She added: “These had to be something that, community by community, people had to work on and vote for. They all had to agree in a particular area and then write it into their deeds.”

Chicago’s versions of restrictive covenants not only banned “any negro or negroes” – which the agreement defined loosely as any person having “one-eighth of more negro blood” – from being “sold, given, conveyed or leased” property, but also forbade Blacks from occupying or even using homes in white neighborhoods “in any manner.”

Their implementation drew the first outlines of what would ultimately become Black Chicago.

Chicago’s Black population was increasing substantially; from 1920 to 1960, it would rise from 44,000 to more than 800,000. Without the legal standing to zonally influence where the new residents settled, restrictive covenants were the primary tool used by white city influencers who, in public, voiced fears of destabilization from outside races they considered “inharmonious” with the homogeny of white neighborhoods, and, in private, harassed and brutalized Black residents.

The use of covenants was not limited to Black neighborhoods – they were also used to cordon off Asian and Jewish communities – but that was their primary application. And because the practice was not only endorsed but encouraged by the Chicago’s influential real estate board, their use was widespread. By the 1940s, roughly half of Chicago’s neighborhoods had restrictive covenants in their housing contracts.

The use of covenants was not limited to Black neighborhoods – they were also used to cordon off Asian and Jewish communities – but that was their primary application. And because the practice was not only endorsed but encouraged by the Chicago’s influential real estate board, their use was widespread. By the 1940s, roughly half of Chicago’s neighborhoods had restrictive covenants in their housing contracts.

“The strategy was to fill one whole block with African Americans, and if they started to spill over into the next one, even if it was a mostly white block, CREB would mark it off and fill it as well,” Satter said, describing a practice called “blockbusting.” “It was massive – contiguous blocks filled with African Americans.”

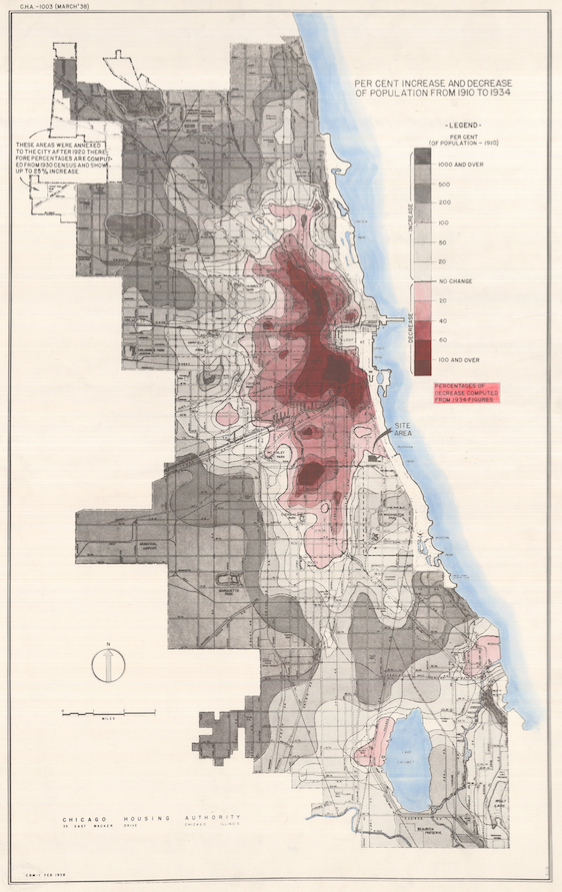

Chicago Housing Authority maps from the time (like the one to the left), which tracked the movement of white populations, show that during the early implementation of racial covenants, white flight took place to an extreme degree in neighborhoods immediately south, west and northwest of the Loop, with many areas losing every single white resident. The boundaries established by racial covenants and block clubs laid the framework for segregation in Chicago.

When Black Was Red

Although local covenants and ordinances were the seeds of housing segregation in Northern cities, it was ultimately the federal government that made it an issue of national policy.

“CREB created a pattern for Realtors to segregate, but the real issue was federal policies and how they worked,” Satter explained.

In 1933, newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), both as part of the New Deal and as an answer to the economic collapse of 1929. Lending schemes in early 20th century America were very different from what consumers encounter today, requiring borrowers to put down anywhere from 30% to upwards of 80% of the home’s cost, all with an understanding that the remainder would be paid off in the five to 10 years that followed. Interest rates were sometimes double or triple what they are today.

There were no federal agencies designated to track foreclosure rates in the beginning of the Great Depression, but estimations often compare levels to those seen during the mortgage market’s collapse in 2007. FDR used HOLC to combat the high rate of foreclosures and provide an easy route for homeowners to refinance their mortgage. But in order to lend, the corporation needed a means to assess risk – or as Satter put it: “In order for the HOLC to make a loan, they first had to define poverty.”

That need for definition marked the beginning of redlining.

“The HOLC brought in local real estate professionals to do the appraisals,” Satter said, explaining how the HOLC began diagnosing financial risk. “And because it was 1933, many were explicitly and overtly racist. The associations were still whites-only at the time.”

To standardize risk assessments, the HOLC established what was ultimately a parochial rating system from the recommendations of local appraisers, which cataloged neighborhoods into four categories: green, blue, yellow and red. Green represented a “homogenous” neighborhood (i.e. white) and the best option for writing a loan, while red reflected a “hazardous” neighborhood, which was almost certainly populated by Black families – hence the term “redlining.” Apart from its correlation to race, the system was arbitrary.

The scope of HOLC was limited: it was only created to help refinance mortgages in default. It was not until the National Housing Act of 1934, which created the Federal Housing Administration, that the HOLC’s risk rating system became the sole basis of evaluating risk for all loans.

“It was ugly; it was arbitrary; and it became national policy,” Satter said.

The primary goal of the FHA was never to keep people in their homes, she explained. The administration’s mission was to “jumpstart the housing industry,” a much broader purpose than the HOLC’s.

“The FHA adopted the risk ratings established by the HOLC, but their agendas were different,” she said. “It wasn’t to give loans directly; it was to insure loans that banks made. It gave banks a safety net so that they would make more loans. The idea was that safer loans meant housing starts would go up again.”

It worked, in a sense. The FHA amortized loans, allowing borrowers to pay off principal and interest over longer periods of time. It encouraged home purchases, and eventually led to the fixed-rate mortgages that are so commonplace today. But in adopting the HOLC’s color-coded rating system (which was then converted to an A-B-C-D grading system), the FHA effectively condoned segregation through lending at a federal level.

“The administration insured loans based on guidelines that were built on a racist appraisal system,” Satter attested. “Even a very well-maintained African American neighborhood could still be rated D, regardless of who was living there, the condition of the homes or the creditworthiness of the people.”

Similarly effective were the FHA’s policies on new construction. Following World War II, the FHA financed mass production of subdivisions across the country, but the agency’s concessionary loans to builders came with a condition – that no homes in the subdivisions be sold to African Americans.

Redlining was not legally barred until the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, but by that point, nearly the entire South and West Sides had been cordoned off as too high a mortgage risk for the FHA to insure loans in those areas – which led to banks not issuing them.

And redlining was not the only force at work orchestrating segregation. Building on its earlier policies of segregated block clubs, the National Association of Real Estate Boards actively warned its members against the dangers of housing African Americans.

In a 1943 brochure, the National Association of Real Estate Boards wrote that Black buyers should be avoided as they may be a “bootlegger,” or a “madame who had a number of Call Girls on her string,” or a “gangster” looking for a “screen for his activities.”

“No matter the motive or character of the would-be purchaser, if the deal would institute a form of blight, then certainly the well-meaning broker must work against its consummation,” the brochure read. Until 1950, the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ code of ethics contained the following canon: “A [sic] Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing to a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individual whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in the neighborhood.”

Check out how those policies changed the demographics of Chicago’s neighborhoods.

Blacklisted: Discrimination in Lending

Housing segregation went beyond limiting the housing options of African Americans – additionally, it bred poverty, a process that, Satter explained, contradicted conventional wisdom on the topic.

“What I’ve found is that after WWII and into the ‘50s, income was actually quite close between whites and Blacks in some areas of Chicago. It was sometimes almost the same,” Satter said. “That’s one of the lies out there, that Black people had poor housing because they were poor. It’s actually kind of the reverse.”

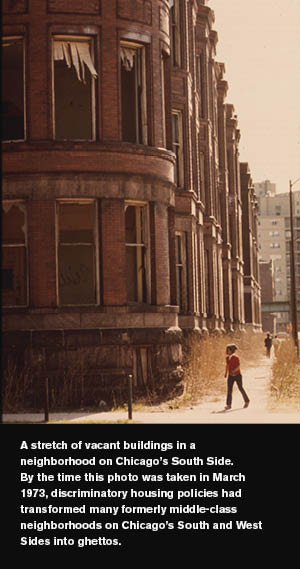

That “reverse” was the high cost of housing, which pushed many Black families into poverty and, with city services such as sanitation and garbage collection lacking, led to the decay of neighborhoods.

The FHA’s promise not to insure loans issued in D-graded districts – which again, were the lowest-rated districts in the agency’s grading system – kept banks from lending to Black families, which left two housing options for the city’s underserved minorities: buy a house on contract directly from the seller or rent in the city’s increasingly crowded, segregated neighborhoods.

A 1938 redlining map from the Federal Housing Administration; all ‘D’ districts, which had majority-black populations, received no mortgage assistance from the government.

Overpopulation – thousands of African Americans were moving to Chicago each month at the peak of the Great Migration – coupled with a housing shortage and lack of protections for minority tenants allowed rents in Chicago’s predominantly Black neighborhoods to overtake those in white neighborhoods. Tenants often paid twice the rent charged to whites. A University of Chicago researcher of the time who studied tenement life in the city, Edith Abbott, wrote in “The Tenements of Chicago” that despite families living “without light, without heat, and sometimes without water…the rents in the South Side Negro district were conspicuously the highest of all districts” she had visited.

With no promise of eventual ownership, many in minority neighborhoods opted instead to partake in “contract buying,” meaning they purchased contracts with independent home sellers who set both the terms and price. In his reporting on the topic, “The Case For Reparations,” journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates described contract lending in Chicago as “a predatory agreement that combined all the responsibilities of homeownership with all the disadvantages of renting – while offering the benefits of neither.”

The white contract sellers were speculators, purchasing cheap homes in previously white neighborhoods and then flipping them to desperate Black families after marking up the price, creating unregulated profit pits. “They would double the price of the home when they sold it,” Satter recalled, “sometimes quadruple it.”

Once a home was purchased on contract, the monthly payments did not translate into earned equity. Tracey Taylor, president of the Dearborn REALTIST Board (DRB) – which African American real estate professionals formed in 1941 to secure the right to equal housing opportunities for Chicagoans, regardless of race, creed or color – explained the high stakes: “If one payment was missed, the owner could and would foreclose on that agreement, and it would be confirmed through the courts. This was a common practice on the South and West Sides of Chicago.”

And the reason for the missed payment did not matter to contract sellers.

“Imagine signing a [contract] agreement,” Taylor said. “Something goes wrong in the property, and the white owner refuses to make the repair, so you make the repair and miss a payment. You are then taken to court and evicted on the spot. What kind of business practice is that to be subjected?”

Worst of all, while contract buying left Black families vulnerable, it also proved highly profitable for the contract sellers. In a 1962 edition of The Saturday Evening Post, one contract seller was quoted as saying, “If anybody who is well established in this business in Chicago doesn’t earn $100,000 a year, he is loafing.”

Satter’s father, Mark J. Satter, was a prominent civil rights lawyer who represented many Black families targeted in contract buying schemes. During the era of contracted homes, Mark Satter estimated that approximately 85% of Black home purchases in Chicago were on contract, and calculated that Chicago’s speculators were robbing the city’s Black population of $1 million a day.

The Contradictions of Affordable Public Housing

In the decades that followed the FHA’s creation, poverty became endemic in Chicago’s overpopulated inner city. By 1960, the poverty rate for African Americans in Chicago was 29.7%, compared to just 7.4% for whites. And the case was nearly identical in Seattle, Baltimore, New York and every major U.S. city with significant minority populations, as Black families were put at a significant economic and social disadvantage.

In response to what the federal government at the time saw as the decline of great American cities like Chicago, a strategy for urban renewal was written into legislation, called the Housing Act of 1949. It was the order that helped build a ghetto within Chicago’s ghetto. The legislation read:

“The general welfare and security of the Nation and the health and living standards of its people require housing production and related community development sufficient to remedy the serious housing shortage, the elimination of substandard and other inadequate housing through the clearance of slums and blighted areas, and the realization as soon as feasible of the goal of a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family.”

Where “the Nation” was written, the legislation meant “whites only,” and where it promised the “clearance of slums and blighted areas,” it really meant the “use of eminent domain to seize and destroy Black neighborhoods.” As Harvard University’s Alexander von Hoffman wrote in his analysis of the 1949 act: “Its history is studded with contradictions. Through its public housing program, the act provided housing for low-income families; through its urban redevelopment program, it cleared slums and destroyed affordable housing units.”

Chicago’s Lake Meadows, a middle-class housing complex erected over the remains of a once-Black neighborhood, is a perfect example. It was transformed into a place its former residents could no longer access. The building was constructed by a private developer, who paid only a fraction of the $16 million it cost to “clear” the land, as Satter put it. The city’s Land Clearance Commission paid more than $12 million to assist the project. The commission wanted the neighborhood, which was close to the city’s downtown, gone.

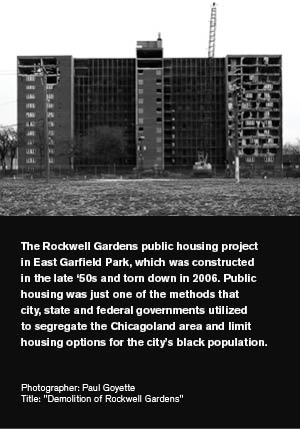

Chicago used the Housing Act to scrub the red from its maps, turning “D” slums into “A” neighborhoods. In doing so, the city displaced thousands of Black families – who it promised to re-house – exacerbating its already considerable population problem. Each city council member had veto power over the placement of new public housing developments in their wards – meaning that aldermen of majority-white precincts refused to allow public housing construction in their areas.

Additionally, the Illinois Relocation Act – a companion to the Redevelopment Act – allocated only enough money to build new public housing for 15% of the displaced. In justifying its decision to fund so few, Satter wrote that the legislature argued “the remainder of the displaced would find housing without aid from the state.” So they ended up in packed public housing buildings in already overcrowded neighborhoods.

“There was vacant land in white areas, enough so that you would not have had to displace people,” Satter said. “But instead they built in already overcrowded Black neighborhoods where they would have to displace even more people to build public housing for displaced people. Segregation was more important than housing people.”

J.A. Stoloff, of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Policy Development and Research, wrote that by the ‘60s, Chicago public housing was among the “most segregated” in the country, and that “the situation in Chicago exemplifies the problems caused by racial segregation.”

When the Fair Housing Act was enacted in 1968, housing segregation through the traditionally legal avenues of redlining and lending discrimination became outlawed. While this came as a welcome change, it still failed to address the residual effects of policies and practices that had defined homeownership in Chicago for nearly a century. It did not, for instance, reverse the damage of blockbusting. The stigma of a Black family in the neighborhood was not erased. The act could not dismantle the interstate roadways Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley had used to cut through slums.

Segregation After Its Outlawing: Sub-Prime Mortgages

The Fair Housing Act also failed in one other area – preventing future cases of housing discrimination.

“Bank redlining is not over,” said Satter, whose current research centers on the finance industry. “There’s no question that subprime lenders as early as the ‘80s, and certainly throughout the 90s and 2000s, were targeting moderate income non-white areas. It’s predatory lending targeted at a particular demographic.”

Research conducted by Jacob Faber, an assistant professor at New York University, determined that in 2006 – just before the collapse of the mortgage market – minority borrowers were 2.4 times more likely to be given a subprime mortgage.

In a recent report, the Chicago Urban League further detailed the effects of sub-prime mortgages on Chicago’s poorest areas, which remain mostly Black and mostly in the South and West Sides.

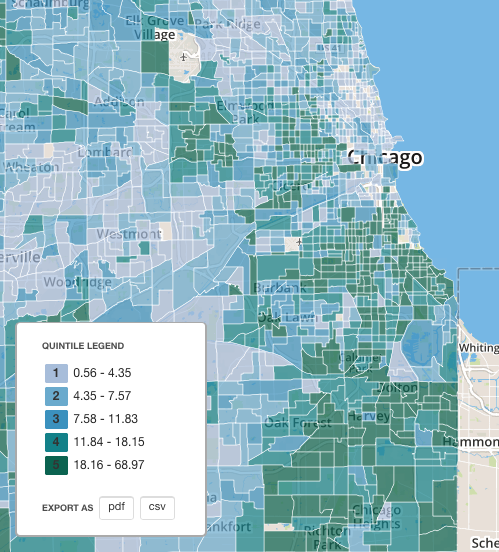

As this map from the Woodstock Institute shows, foreclosure activity in 2014 was heavily concentrated in Chicago’s West and South Sides, where subprime lending was most common.

The report stated that through each phase of the mortgage crisis, African Americans were calculably disadvantaged. Before the crash, they were more likely to receive high-cost subprime loans; following the crash, they were less able to secure mortgages for home purchases; and after the foreclosure crisis, Black buyers had “significantly less access to home refinancing loans, making it difficult to bounce back financially from harmful subprime loan products.”

From the housing bubble’s peak (between ’05 and ’07) to the market’s recovery (between ’12 and ’14) mortgage activity fell throughout Chicago by an average of 64%. However, in neighborhoods the Urban League describes as “racially concentrated areas of poverty” (RCAP), even the best performing neighborhoods saw more acute declines. In Riverdale, mortgage activity over the same time period dropped 95% – only 13 mortgages were issued to the neighborhood between 2012 and 2014. Activity fell by 94% in Fuller Park, and 92% in Englewood and West Englewood. The least affected of the 19 RCAPs evaluated was Oakland, where mortgage activity still dropped 69% – five points above the city’s average.

The Social Cost of Segregation

Earlier this year, Brookings Institution Demographer William Frey’s reported that Chicago is currently the third-most segregated city in the country, behind Milwaukee and New York. Frey stated that 76% of the city’s African American population would have to move to achieve complete integration.

An average white citizen in Chicago today lives in a neighborhood that is nearly three-quarters white. By contrast, the average Black citizen lives in a neighborhood that is 64% Black. That may be down from 69% in 1960, but the systematic subjugation of minorities in Chicago has created boundaries that transcend geography.

Income Disparity

From 1970 to 2010, data from the U.S. Census (organized by the University of Toronto) shows how strongly the direction of income growth or decline in Chicago has correlated to neighborhoods.

In large swaths of city, mostly found in the South and West Sides, incomes over the four-decade period averaged not growth but decline, with drops ranging in varying degrees of severity from 20% to 114%. On the city’s predominantly white North Side, incomes were up in some places by as much as 254%, and never by less than 20%. Using data from the American Community Survey, which is based on the latest available Census tract data (2008–2012), online income mapping site Rich Blocks Poor Blocks found that median incomes in the South and West Sides ranged from less than $10,000 to $39,999, while North Side medians ranged from $60,000 to $99,999.

Moreover, a study from the Brookings Institution confirmed that, regardless of neighborhood, the incomes of white Chicagoans grew by 52% from 1990 to 2012, compared with just 13% for Blacks and 15% for Hispanics.

Additional research shows the generational effects behind those statistics.

Additional research shows the generational effects behind those statistics.

Earlier this year, a paper released by a team of researchers led by Stanford economist Raj Chetty reaffirmed the barriers to wealth that poor children inherit from their parents, and added credence to the widely supported belief that where people come from will play a significant role in determining where they will end up. The study showed a particularly bleak outlook for low-income boys.

“Low-income boys who grow up in high-poverty, high-minority areas work significantly less than girls,” the report read. “These areas also have higher rates of crime, suggesting that boys growing up in concentrated poverty substitute from formal employment to crime.”

Furthermore, a study by Columbia University’s National Center for Children in Poverty found that 45% of people who spent at least half of their childhood in poverty were poor at age 35. For those who spent less than half of their childhood in poverty, only 8% were poor at age 35.

In 2014, The New York Times mapped poverty levels for several major U.S. cities, and found that in Chicago, the South and West Sides were steeped in poverty, with 40% to 60% of residents living below the line (which was set at $23,283 for a family of four and at $11,945 for an individual). In some areas, such as Englewood, the poverty rate was above 60%.

The Health Gap

“The reason we pay so much attention to segregation is because it matters in terms of life outcomes,” Stephanie Schmitz Bechteler, research and evaluation director at the Chicago Urban League, recently told the Chicago Tribune. “Where you live and where you grow up matters, and so does who you grow up around. It dictates where you go to school, the access you have to healthy business corridors, even your access to healthy food and job opportunities. All of this is tied to your address.”

Life expectancy is among the outcomes affected by location, according to data compiled by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Around the Loop, life expectancy is 85 years; around the Red Line stop at Fullerton, on the North Side, it’s 81 years. But to the west, in East Garfield Park, life expectancy drops to 72 years. Further south near Washington Park’s Garfield Red Line station, it falls even lower to 69 years.

In a 2015 article from The Huffington Post, Harvard Medical School Professor Karen Winkfield told the publication that health disparities between whites and Blacks are “universal.”

“There are disparities across almost every single disease entity,” she said.

According to figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, African American children are more likely to be obese and have asthma, and Black populations are, in general, more likely to develop (and die from) breast cancer and contract HIV.

In an interview with the Tribune, Steve Whitman, of the Sinai Urban Health Institute, linked Chicago’s health gap to segregation.

“The underlying issue here is racism and poverty,” he said. “In Chicago, it’s exacerbated by segregation. Black people in Chicago are forced to live in neighborhoods where…they tend to go to segregated health facilities that are poorly funded and, in different ways, failing.”

Dearborn REALTIST Board President Tracey Taylor also draws attention to the far-reaching legacies of the city’s housing discrimination practices.

“Those unlawful practices are still impacting African Americans today,” Taylor said. “Decades of systemic bias and unlawful real estate business practices have denied us the right then and, to a certain extent, continues to do so today. When you have a property that is equal distance to downtown Chicago, but the values are not equal, there is a huge disparity. Property valuation is key in determining the worth and economic development potential in a given neighborhood. If the playing field is not level, it’s an economically devastating loss for that community.”

Resistance, Past and Present

Early, successful challenges to Chicago’s rampant segregation included a group of Black contract buyers in the South Side, who formed the Contract Buyers League and successfully campaigned to outlaw predatory contract lending. Additionally, there was a series of court cases collectively known as Gautreaux, which spanned the decade between 1966 and 1976. The cases took on the Chicago Housing Authority and its discriminatory public housing policy, and eventually forced the city to issue thousands of Section 8 housing vouchers that allowed residents to break through half-century-old racial barriers and move into the mostly-white suburbs.

But segregation is still alive in the city.

“Effectively addressing our city’s segregation disparities requires new approaches,” wrote Shari Runner, president of the Chicago Urban League, in an op-ed published in Crain’s.

In the Urban League’s report, the group offered a comprehensive action plan to combat the damaging, residual effects of a century’s worth of racially-based housing policy. The plan promotes community investment at the municipal and community level; bridging communities by identifying and disassembling mobility barriers (like unfair housing policy); creating sustainable land-use patterns and focusing transit development on the South and West Sides; improving accountability and transparency throughout local government and related housing agencies; and developing a strategy for the proper planning and oversight of handling the city’s surplus of vacant and at-risk properties.

“Solutions must be initiated and driven with intent by people who are on the front lines of this disparity, including those from the city and the housing,” Runner said.

Taylor also emphasizes the importance of listening to individuals on the front lines.

“As a longtime resident of Chicago, I’ve heard rhetoric to address the economic problems in minority communities, but I have seen very little manifested,” he said. “Chicago is a very segregated city, and the city leaders feel giving a label of ‘diversity’ to this city sounds good – in reality, that’s a code for segregation. The Black and brown citizens have a higher unemployment, lower life expectancy and limited mobility than our counterparts. I think if our leaders would listen to the community organizations and community leaders, and leave the status quo alone, perhaps some changes could take place.”

For its part, the DRB is very engaged with the housing needs of Chicago’s African American communities, offering classes for members/consumers; seminars on financial literacy and homebuying education; non-real estate events on increasing consumer income streams; and forums with elected officials. Such initiatives, Taylor explained, are integral to the board’s founding purpose.

“We were founded in 1941 because African American real estate professionals were not allowed to become members of the Chicago real estate board,” Taylor said. “The DRB has been fighting unlawful real estate practices towards people of color for 75 years. We are committed to leveling the playing field, and it is the hope of this board that this industry embraces this commitment.”

Brian Bernardoni is one member of the industry embracing those commitments. He is the senior director of governmental affairs and public policy for the Illinois Association of Realtors.

“It’s at the core of our practice to make sure that our Realtors follow our code of ethics,” said Bernardoni. “The association also makes sure that its members follow not only the intent, but the rules and wording of the Fair Housing Act.”

Article 10 of the Chicago Association of Realtors’ Code of Ethics states members’ obligations to their clients very clearly:

“Realtors shall not deny equal professional services to any person for reasons of race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status, national origin, sexual orientation, or gender identity. Realtors shall not be parties to any plan or agreement to discriminate against a person or persons on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status, national origin, sexual orientation, or gender identity.”

“It is not a good situation for a Realtor to find themselves out of compliance,” Bernardoni said, eluding to stiff penalties not only from the association but also, depending on the circumstances, from the city and state. “We handle incidents of discrimination through our professional standards and complaints department. But we can only enforce what we hear about. If a violation takes place and we’re not notified of it, the association doesn’t have the authority or wherewithal to act. And I don’t believe the membership would want the association scrutinizing every transaction to look for what might be a violation.”

Bernardoni described fair housing as “critical,” and explained that to keep members compliant and aware of what “fair” entails – something he said has changed over time to now include veterans and the LGBT community – the association includes fair housing education in its orientation program and further requires that all members retake the course on a quadrennial basis.

The association’s efforts are a means to combat segregation at a grassroots level. But as Satter explained, they do not solve segregation, not completely, because segregation is not solely a grassroots problem. It’s bigger than that, more systemic. Ultimately, it is a federal issue.

“I don’t think a local institution can turn the tide of segregation alone,” Satter admitted. “It needs to be challenged, overtly and explicitly. White people need to be challenged to understand why their neighborhoods seem better. That means firmly grasping the history in order to alter it.”

Expert Sources

Brian Bernardoni is the former director of government affairs and public policy at the Illinois Association of Realtors in Chicago. He is also a past national chairperson of the National Association of Realtors and, since 2003, has raised over $2.0 million for RPAC, the Realtor Political Action Committee.

Brian Bernardoni is the former director of government affairs and public policy at the Illinois Association of Realtors in Chicago. He is also a past national chairperson of the National Association of Realtors and, since 2003, has raised over $2.0 million for RPAC, the Realtor Political Action Committee.

Beryl Satter is a professor in Rutgers University’s Center for Migration and the Global City. Her book “Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America,” won the Liberty Legacy Award in Civil Rights History and the National Jewish Book Award in History, and it was a finalist for the J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize and the Ron Ridenhouer Book Prize.

Beryl Satter is a professor in Rutgers University’s Center for Migration and the Global City. Her book “Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America,” won the Liberty Legacy Award in Civil Rights History and the National Jewish Book Award in History, and it was a finalist for the J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize and the Ron Ridenhouer Book Prize.

Tracey Taylor is the former president of the Dearborn REALTIST Board, the former National Association of Real Estate Brokers Chicago Chapter president and the managing broker/owner at T.N. Taylor Realty. He has more than 20 years of experience in real estate.

Tracey Taylor is the former president of the Dearborn REALTIST Board, the former National Association of Real Estate Brokers Chicago Chapter president and the managing broker/owner at T.N. Taylor Realty. He has more than 20 years of experience in real estate.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article was originally published on March 16, 2016.

Excellent article! Very well written and researched.

Excellent article. I had heard stories about this from my mother. It’s great to read about it. Well done!

excellent written article and very informative

This is a wonderful article that was well written and researched. it gives a great historical perspective and lesson on Fair Housing practices of today. NOW, what we need is an article on the disparity of opportunities among minority agents in the more thriving communities. We need to also look at how we view “opportunity” areas and areas that get more marketing and news time in real estate publications as a result of a different form of discrimination directly related to the fair housing.