The sign puts it frankly: “This home at 6823 S. Aberdeen was legally stolen from black couple Mr. and Mrs. James and Lula Malone on October 30, 1963 in a widespread land sale contract scam.” Situated in front of the property in question, a vacant home in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood, the scene tells an even larger story of inequity. One that is ongoing and embedded into the block.

Local artist and activist Tonika Lewis Johnson installed that sign, and others across Englewood, as part of a project titled “Inequity for Sale.” Aiming to expose how the effect of land sale contracts during the 1950s and ‘60s is still visible today, Johnson’s work has made headlines. And her recent podcast “Legally Stolen” offers listeners an even deeper historical dive.

Produced in conjunction with the National Public Housing Museum (NPHM), “Legally Stolen” is a podcast in three parts which culminated in a live event on April 28, presented by WBEZ at King-Kennedy College. There, Johnson was joined onstage by co-host Tiff Beatty, the NPHM programming director, as well as two expert panelists: Amber Hendley, co-author of the study “The Plunder of Black Wealth in Chicago,” and Marisa Novara, commissioner of the Chicago Department of Housing.

Chicago’s history of land sale contracts

The evening at King-Kennedy College kicked off with an explanation of the practice in question: land sale contracts, which were widespread in Chicago’s black neighborhoods during the 1950s and ‘60s. As local black families were precluded from traditional bank mortgages due to redlining, these contract sales were an apparent alternative. They offered the illusion of mortgage payments — but with none of the typical protections.

As the first step in the contract process, real estate speculators snatched up homes with low property values. Amid the so-called “white flight,” these houses were purchased cheaply, often from families desperate to exit increasingly non-white neighborhoods. Then, the homes were sold “on contract” to incoming black families for an average markup of 84%. But the contracts were a scam.

In addition to the high value of each contract home, monthly payments were set at a high interest with no equity. And if owners defaulted on even one bill, they could — and often did — legally lose the property, along with everything paid into it.

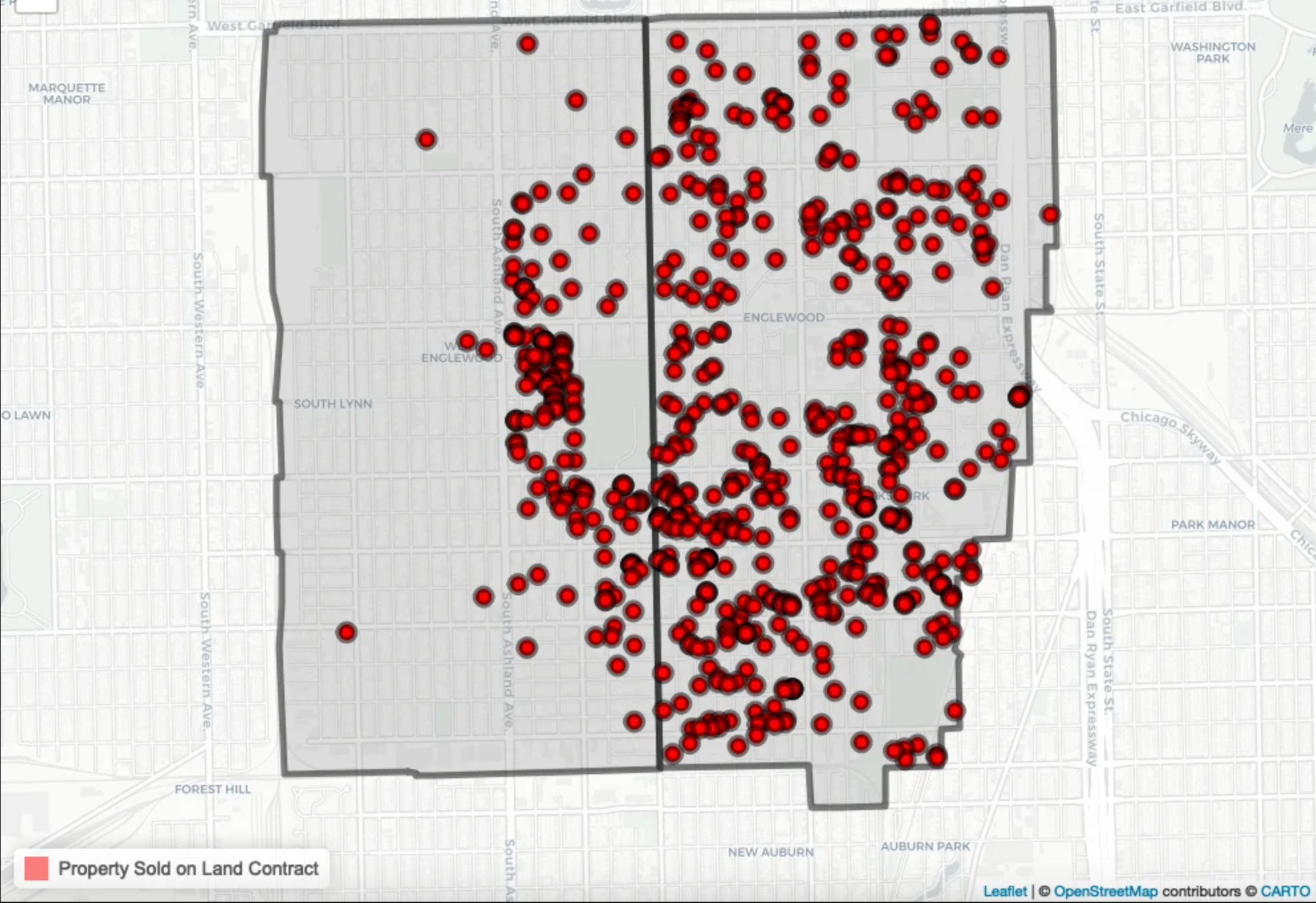

In total, over 600 homes in Greater Englewood sold on land sale contracts. See them scattered across Chicago’s South Side on the map below, courtesy of the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University

“The Plunder of Black Wealth in Chicago”

Homes sold on contract in Greater Englewood between 1950 and 1975, from Johnson’s website.

The map, compiled for the study “The Plunder of Black Wealth in Chicago: New Findings on the Lasting Toll of Predatory Housing Contracts,” visually illustrates the wide scope of land sale contract transactions. And it was this image which first inspired Johnson to create, and plant, her “Inequity for Sale” signs.

Johnson discussed the map — and the intense reaction it stirred in her — with fellow panelist Hendley on Thursday night. Hendley co-authored the study in 2019 and went on to personally coordinate with Johnson, providing the artist with a full list of addresses for Chicago’s land sale contract locations.

And although her academic work garnered positive attention upon its publication, Hendley said, it was Johnson’s signs which sparked the public discourse. The “Inequity for Sale” project was featured across local media outlets, from NBC 5 to the Block Club Chicago, as it offered an unmistakable visual — and physical — representation of history. Like the map which inspired them, the signs highlight a systemic inequity, Hendley explained, as opposed to the perception that abandoned or run-down homes are simply the result of the individual failures of their owners.

Hendley also offered a more comprehensive look at the repercussions of land sale contracts, based in numerical data. As the “Plunder of Black Wealth” researchers determined, a combined total of $3.6 billion was stolen from black homeowners under land sale contracts (adjusted for inflation). And that is a decidedly low estimate, Hendley added, conjecturing the number may well be closer to $4.6 billion.

That massive theft was also compounded by the racial wage gap, even more rampant at the time, with black families earning 57 cents on the dollar to white families, Hendley said. As an obvious result, the quality of life was severely diminished in affected neighborhoods. And yet, Hendley said, black homeowners maintained a default rate of just 17% despite their predatory contracts. A fact which, in a particularly emotional moment, she attributed to the resilience of black Chicagoans.

Those statistics, along with their cultural consequences, are discussed further in the “Legally Stolen” podcast, available now on the NPHM website and other streaming platforms.