The Federal Housing Act has helped curb housing discrimination since the late 60s. A new lawsuit could see to extend those protections or limit them.

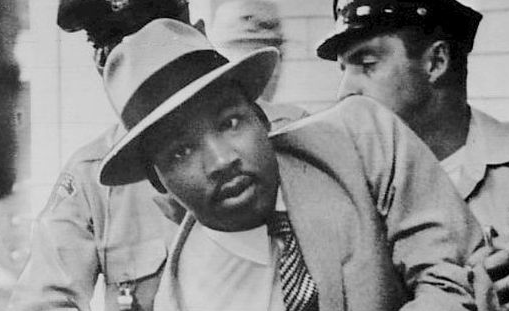

Martin Luther King Jr., whose death helped galvanize the nation and inspire a wave of landmark civil rights laws.

On April 4, 1968, a historic date by any measure, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was shot dead on a second-floor balcony in Memphis, Tenn. King’s death, while a tragedy mourned the world over, ultimately became a catalyst for action, galvanizing lawmakers, helping to spur the creation of some of our nation’s most fundamental civil rights legislation to address a plethora of discriminatory standards, including those in housing.

Shortly after King’s assassination, President Lyndon Johnson compelled Congress to act, specifically urging the expedited passage of the Fair Housing Act, which promised to combat a housing process wrought in discriminatory practices. The act was signed into law before the icon’s funeral.

Earlier this week, the continued relevance of the FHA came into question as the U.S. Supreme Court argued whether to uphold the longtime law.

Picking up a case filed by Texas-based group Inclusive Communities Project, the nation’s highest court discussed whether the protections of the FHA should extend to minorities who’ve been segregated to neighborhoods as a result of tax credits. During discussions last week, the group claimed the state’s tax credit policy has a disparate impact on minorities; and that even if the defendant didn’t act with discriminatory intent, the policies themselves were damaging enough to warrant federal protection.

The current understanding of FHA is that the law protects minorities from discrimination by landlords or home sellers. However, the legislation doesn’t explicitly provide security against policies that might impose inadvertent harm, which is the point of contention.

In 2008, ICP sued the Texas Department of Housing and Community Development on similar accusations of segregation. After reviewing ICP’s arguments in appeals, a federal court determined the group hadn’t enough evidence to prove intentional bias from Texas officials, the Associated Press reported, but did agree the policies in question had a disparate impact on the area’s black residents.